|

|

|||

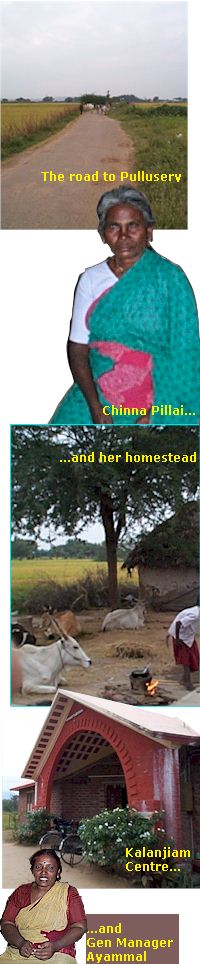

Kalanjiam, the micro credit movement that started near Madurai is opening new doors for poor women. |

|||

|

Alagar Kovil is a detour enough from Madurai. From there, Pullucheri is even further removed. It is one of the millions of small settlements amidst fields, hills and woods of India that you don't see as you ride your car or train. Here unknown numbers toil and die. Change and progress are rare and reluctant visitors to these places. But for a decade now, development activists have been reaching these hamlets with plans for prosperity. From all over India stories of transformation of village economies are beginning to emerge . Small successes are being replicated in ever widening areas, and in some cases 'change' is spreading with the ferocity of forest fires. 'Dhan' comes calling: One such fire began about 10 years ago in Pullucheri. For centuries, the hundreds of acres near Alagar Kovil have been owned by a few landlords. To work their farms tiny settlements like Pullucheri grew up, where folks, labelled with the ugly phrase 'Scheduled Castes' lived. They were landless, marginal or contract labourers dependant on this trinity : landlord, money-lender and monsoon. There has seldom been overt oppression, but in its place was a crafty, benevolent blind-folding. It was normal for the landlord to dictate and arbitrate. It was normal if people sickened and died. It was normal for children to grow up with no education. It was normal to hock your future to borrow money. It was normal to pay upwards of 300% as interest. It was normal to enter old age at forty or fifty, and wait for death. Chinnapillai-- an 18 year old girl-- married Perumal and came to Pullucheri, just over 30 years ago to this life of unquestioning acceptance. Perumal was soon a father of many, deeply into debt and broken down by hard work. Chinnapillai had worked as a labourer ever since she was a child and by early 1990s was a supervisor of a small group of women, whose work she was answerable for. It is now clear she was different from others. "I was polite", she says. "but always nagged the landlord for better wages for my flock." Chinnapillai acquired a reputation of being a battler. In this little known village arrived, in 1990, Sumathi, Usha Rani and Vasimalai. These very obvious 'town-folk' spent some days prowling around and taking notes. They asked questions and came on friendly. The villagers were curious but on guard. Recently a smooth talker had collected their money with many promises and had fled, never to be seen again. When Vasimalai after some weeks of building relationships, proposed a savings group their worst fears surfaced again. Chinnapillai strikes a match: M. P. Vasimalai, is of a phenomenon that began in the late eighties. He had passed out of the Indian Institute of Management [Ahmedabad]. A wide buffet of upper crust jobs was on offer. But he like several of his generation, chose to return to small-town India, from where to look for situations in which they --with their trained skills-- could matter in a pro-active way. Formal courses designed to take modern management tools to rural India had been started in 1979 by the redoubtable Dr.V.J.Kurien of Amul-fame. His Institute of Rural Management in Anand, Gujarat pointed to a lacuna in India's development strategy and sought to fill it. Inspired by that initiative -- and no less by the man himself-- many young men returned to work at the grass-roots. Vasimalai was one of that few but significant number. He now heads the Dhan Foundation. The simple folk of Pullucheri were not easy converts to the idea of growing big through small savings. They had been, as we saw, stung once. It was the strength of personality of Chinnapillai that carried conviction in the end. Once she was persuaded, she led her group to form the first savings unit: PullukKalanjiam, short for 'the Granary of Pullucheri'. Ten women began to contribute Rs.20 per month. The collected sum was lent to a group member most in need of it. They charged an interest of 60% per annum. "It was a high rate", she admits. "but a fraction of the going rate. And nothing needed to be pawned. They were thrilled and incredulous!" In six months, their Kalanjiam was lending the astounding sum of Rs.1000 per month. Group members could meet emergencies or start small enterprises. Chinnapillai and her pioneer friends began to travel to villages nearby to spread the gospel of their Kalanjiam and how there was 'big' money to be accessed. Local Kalanjiams --each never exceeding 20 women-- sprung up in Matthur, Kunnathur, Chettipulam; often five or six in each village. The fire that Chinnapillai lit had taken hold. Modern gaze: Dhan's approach from the beginning was to build a strong organisational structure based on simple but thorough record-keeping. This led to total transparency and confidence in the movement increased. Meetings were regular and minuted. Every issue was debated and decisions were consensual. Rules were rigorously enforced. Dhan's workers stood back but always directed the modern light of sound management practices on Kalanjiams' work. They also trained the women who fanned out to spread the idea. By 1993, there were enough Kalanjiams to merit formation of a federation: Vaigai Vattara Kalanjiam [Federation of Vaigai Area Kalanjiams]. Chinnapillai was of course, the unanimous choice for President. Office bearers marched into government offices and banks. They asserted themselves to access the schemes the governments had announced. They presented their systems and activities to banks. Canara Bank got interested: here was a risk-free roster of women who could be lent money. After all the Federation stood guarantee for the return of loans. Here's a delightful aside: money is never lent to a woman whose husband drinks! For the family to qualify, he has to reform. Kalanjiam finances his detoxification programme at a modern centre in Madurai. So far 48 have quit the bottle, with zero relapses. Individual loans of the size of Rs.50,000 began to happen. As long as the applicant was a member of a Kalanjiam, had an unblemished record of subscription and repayment and her reasons for a loan was seconded by the Federation, the bank came up with the money. Credit began to flow for setting up shops, digging wells, buying land and livestock, to build houses, to buy threshers and carts and so on. The Federation holds regular annual general meetings [AGMs]. In 1996, Dhan invited the Tata group to send observers to the AGM. The scene stunned them. 2000 women gathered for a day-long festive business meet in an open field. They presented reports and audited accounts, moved resolutions and debated issues, made speeches, proposed ideas and schemes. Tatas swiftly donated Rs.26 lakhs with which to build a Centre office, to start 100 more Kalanjiams and address health matters. The score today: Today the sharply etched Vaigai Vattara Kalanjiam Centre, at Appan Tirupathi, built in the Laurie Baker style is abuzz with activity. It runs training courses for emerging Kalanjiams and watches over existing ones. It is the voice that speaks to the outer world. It has a well paid Managing Director and a computer trained staff of 6. They are needed indeed: there are 4000 members in 246 Kalanjiams spread over 88 villages that lie under 46 panchayats. Ayammal is the General Manager with a salary of Rs.1800 per month. She studied only up to the sixth standard but is a reminder of how quickly Indians learn skills on the job. She audits the record keeping practices of all Kalanjiams and administers the Centre. "You know, we have about Rs.3.5 crores [over a million dollars!] going around among members", she says. "We can't afford any irregularity." In the meantime, Chinnapillai has been going places. She travels far and wide speaking on self-help, savings and credit. The Kalanjiam idea has spread to Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. She was one of the five women who won the Stree Shakti Puraskar for 1999. She flew to Delhi to receive it from the hands of Prime Minister Vajpayee. "I don't know what came over me. There was something about him that moved me to bend down and touch his feet. So I did that", she says. Vajpayee must have felt like-wise about this dust rose: he bent down and touched her feet in return. Vaigai Vattara Kalanjiam Appan Thirupathi Post Madurai 625 301 Tamil Nadu Phone: 0452 -470212 Dhan Foundation Phone: 0452 -610794 email: dhan@md3.vsnl.net.in Getting there: Driving from Madurai towards Alagar Kovil, Appan Thirupathi is about 30 km and Pullucheri is about 4km off the main road. February,2002 |

|

||