|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The mission of India's Green Revolution may have been to give it time to plan its long term strategy. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

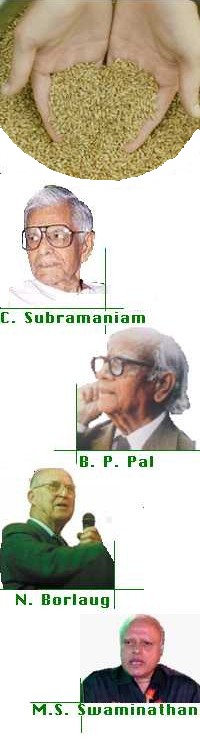

India's food-grains production has hovered around a fifth of a billion tonnes mark in recent years. More than self-sufficient, India frequently exports its surpluses. India in 55 years has emerged from famine ridden colonial times, as a famine free Republic. Its population has nearly tripled in that period. More significantly, India in 1947,lost some of its most fertile lands. But she has managed to stand up and falsify many prophesies of doom. India was the greatest success story of the Green Revolution. Although today her agriculture is at a cross-roads again, the Green Revolution of the sixties gained some crucial decades for India in which to rethink her way forward. The Revolution is also worth remembering for India's capacity for collective action. Pause a while therefore, before you decry India's administration for every ill in the land. Famine kingdom: If the shame of the German Reich was the Holocaust, the British Empire --the Reich's great adversary-- matched it with the Bengal Famine. Both occurred around the same time and the scores were about even: 3 million dead in each. As a consequence of heartlessness and inept governance, the Great Famine of 1943-44 has no equal. Heavily taxed and left to themselves and the monsoons, India's farmers began the forties with falling, failing crops. The 'war effort' meant seizure of farm produce, banning of grain trade and turning the gaze away from the countryside. Result was, destitute folk began to arrive in Kolkata looking for food. Fearing that declaring an official famine would mandate supplying food diverted from its armed forces, the Empire simply let people die in the streets. And then within three years, with the war won, the British upped and left a traumatised, dismembered India. The young nation was the object of much mockery world-wide. "Starving millions" was the phrase flung at it for an identity. Though the Indian farmer was back plying his heartache trade, shortages recurred. India was a massive importer, the tonnage peaking at 10 million in 1966. Humiliation was heaped upon it in a book : "Famine 1975" [Paddock and Paddock, 1965]. The authors predicted that by 1975 Indians would die in their millions. They suggested that the world turn its attention away from this hopeless land. Thomas Malthus probably concurred from his grave. Many nations of course helped, notably the USA with its massive PL-480 programme. The Indian government gamely coped with the times. It was a decade of much hardship and morale sapping pessimism. The tide turns: The story of how what came to be called the Green Revolution began is an exciting one. The story's moral is that hope is always buried within tragedy. Shortly after the Bengal Famine, MacArthur's victorious US army marched into Japan. In the huge occupation force was S. Cecil Salmon of the US Agricultural Research Service [ARS]. Many initiatives were being considered for rebuilding Japan. Salmon was focused on agriculture and that was how he chanced upon the legendary Norin strain of wheat that was to trigger the Revolution. Norin was a dwarf variety with little foliage and a heavy head of grain. Salmon sent this to the US for further study. In Washington State University at Pullman, a team under Orville Vogel researched the dwarf wheat. They bred many prototypes and finally created in 1959 the Gaines dwarf. It had been 13 long years of experimentation. Norman Borlaug --that icon of the Green Revolution-- picked up Gaines and crossed it with Mexico's best varieties at the International Maize and Wheat Research Centre there. He had the magic bullet -- he waited to unleash the Revolution. By the 1960's India was desperate for a breakthrough. The nation's self-confidence was at an ebb. The Chinese had delivered a military lesson. Nehru was aging. Political uncertainty loomed. Food crises were endemic. Total food production hung around about 50 million tonnes. Marginal increases were only through bringing more land area under cultivation and not through increases in productivity. Food reserves were nil. India was just about meeting its deficit with imports. Clearly a quantum leap was needed. It was then that India discovered Borlaug and the Norin dwarf. A small field at Pusa was seeded and the results were dramatic. It was what India had been waiting for. What then followed was a display of commitment and implementation that has stood to inspire India in many other fields. It is a milestone to cherish. Though the Green Revolution was a worldwide phenomenon its most successful revolutionaries were India's political leadership, bureaucrats, scientists and of course the farmers. What it took: Once Borlaug and India were convinced that they had a solution, the realisation of what needed to be done dawned. It was a formidable task. But India had its men in place. Of the ones that are easily named are C. Subramaniam, B. P. Pal and M.S.Swaminathan. In the end however, literally millions of Indians were active parts of the Revolution. C. Subramaniam was in 1965, the Union Minister for Agriculture. He had trudged a long road, as a Gandhi devotee, freedom fighter and as a member of India's Constituent Assembly. Most of all he was a modern mind and a man of action. Swaminathan was an entirely home-grown plant genetist of repute. He emerged as Subramaniam's able lieutenant. In 1996, Subramaniam took the politically bold decision of importing 18,000 tonnes of the dwarf wheat seeds of the Lerma Rojo 64A and Sonora 64 variety. The induction of an agricultural technology is not a mere question of buying seeds. Conducive policies and delivery systems have to exist. Subramaniam piloted the necessary reforms. To disseminate information Krishi Vigyan Kendras, model farms and district block development offices were put in place. Seed farms were developed. To augment research the Indian Council for Agricultural Research [ICAR] was reorganised. As the dwarf variety was chemicals and fertiliser intensive new industrial units were licenced. To encourage two crops a year and monsoon-independence, irrigation canals and deep water wells were created. Policy was changed to assure guaranteed prices and markets. Food stock storages were created. The results were not long to come. Land under active cultivation began to grow from 1.9 million hectares [mHa] in 1960 to 15.5mHa [1970], 43mHa [1980] and 64mHa [1990]. As for the Paddocks' prophesied demise of India in 1975 well, it didn't happen: India weighed in that year with over 110 million tonnes of food grains.

It is also well to remember that India continued its own adaptive research on high yielding varieties [HYV]. The Revolution was not about just importing seeds. At the Indian Agricultural Research Institute [IARI], Benjamin Peary Pal developed the New Pusa 809, a hardy Indian wheat variety. A genial man who did his doctorate at Cambridge in 1933, B.P.Pal is easily the father of post-modern research in India's agriculture. He was a painter, a rose fancier and a patron of arts. He built a large team, groomed many scientists and extended the HYV research in crops other than wheat. Indian Council for Agricultural Research [ICAR] of which he was the first Director General, proceeded to synthesise and broadcast many HYV seeds like Pusa Sonara, Malavika, Kalyan Sona. Many of these are popular today in Pakistan, other SAARC countries, Afghanistan, Sudan and Syria. The success was not agriculture's alone. There were many spin-offs. Infrastructure improved. With increasing production India paid back all her loans on time; this increased its standing in the world. Vast employment opportunities opened up. Demand for consumer and industrial goods were triggered. Science-mindedness --and mechanics!-- sprouted everywhere. Amazed by the doughty farmers of Punjab and Haryana --the real real heroes of the Revolution-- Canada came wooing them to settle and farm its lands. Indians came to esteem themselves better. India had shaken off her colonial hang-over and defied the mould assigned for her. The next road: So let us say, "Long live the Revolution!" Why? Is it dying? No, but no Revolution is permanent. We began by observing that 'hope is always buried in tragedy'. Maybe strife in return arrives with success. The Green Revolution has thrown up its own set of problems. There has been a toll on soil fertility. The HYVs call for heavy dosages of chemicals -- fertilisers and pesticides. Prolonged use of these has depleted our soils and poisoned our environment. The once thrifty farmer has become a profligate user of power and water. Also because this form of agriculture is capital intensive, it is the farmer of means who most benefits from it. Therefore, while India's food problem may have been solved, not so the hunger problem of its poor. The profits of the Revolution have not spread evenly in society and the poor have little means to buy the huge stocks with the government. Worst of all yields are beginning to fall. We may have basked for too long in the glow of the Revolution. So, India is at a cross-roads again. Which road is it to take. A tempting sign points to transgenic crops, also known as genetically modified [GM] crops. These are promoted as being the spear-heads of the next Green Revolution. They are said to need fewer inputs, display greater immunity to pests and yield high. But there are many sober voices that dispute these claims. Their views too are justified because in the past, multi-national companies have hastily jumped in to reap their profits with dubious products leaving the farmer to harvest sorrow. Objective scientific assessment of the claims made for GM crops is not yet complete. So the time may not be ripe yet to induct these promising technologies. The more sensible road to take is the one to eco-sensitive farming. India needs to reevaluate proven, ancient ways of harmoniously maintaining soil fertility. Dependance on chemicals has to be minmised. Esteem for carefully selected native strains has to be encouraged if the small farmer is to be freed from malevolent seed companies. Conservation and optimal use of water is an important issue. Most of all, agricultural pricing and market policies need to be reviewed to favour the small farmer. There are signs of an emerging awareness all around. Many farmers in Kerala and Karnataka are turning to organic farming on a large scale. Most significantly Swaminathan, that star of the Green Revolution is today an advocate of 'sustainable agriculture'. So let's put the Green Revolution in context again. It is undoubtedly a great Indian success story. But its unspoken mission may have been to give us a fresh breath with which to codify Indian farmers' traditional wisdom. Today technologies and Indian technologists are available -- as was not the case in the sixties-- to compile 'best practices' and disseminate them widely. It is in the nature of revolutions that they are never 'final solutions' but place-holders till the next one comes along. One of the best summaries of Indian agriculture since the sixties is the one available from the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, from which most of the statistics in this article are drawn. November,2002

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||