Rural folks' cancer deaths are less talked about than their suicides, but the scale and causes are the same.Since 1997 Dr Debal Deb has been conserving 700 varieties of native rice that seed companies are trying to drive outAnshu Gupta's volunteers driven Goonj, collects, sorts and distributes clothes for the poorFor over a 100 years Olcott Memorial High School in Chennai has been giving free education to the poor.

The 10 Guntha Project:

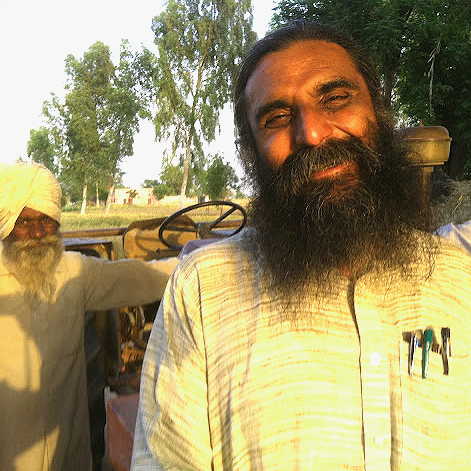

Guntha is a traditional measure of land in Maharashtra. 40 gunthas make an acre. Shripad Dabholkar's critical analysis of the interaction between plants, sun light and physical organic requirements convinced him that 'modern' agriculture was wasteful and unprofitable, and therefore forbidding.

If one were truly scientific, farming can be simple and profitable. Dabholkar called it Natu Eco [pronounced, 'natcheko'] farming. It is this knowledge that he took to the farmers of Maharashtra, to revolutionise grape and mango growing in small lots all across the state. One of his revolutionary beliefs was that a family of five can live well on 10 Gunthas or 1/4 acre.

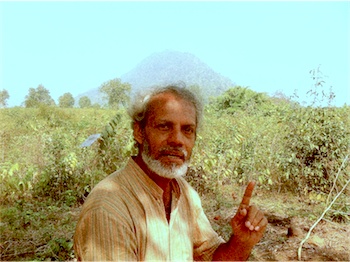

G.G. was a great friend of Dabholkar and sought him out to do something for poor Adivasis who are generally left to fend for themselves on marginal lands. After Dabholkar's death, his long-term disciple Deepak Suchde has been a passionate evangelist of Natu Eco farming. At the Yusuf Meherally Centre, Deepak Suchde, funded by the Dr Malpani Trust, has established a pilot 10-G project to demonstrate its premises. These can be summarised broadly as follows:

§ Almost any terrain can be farmed : roof-tops, barren rock and derelict land. All you need is access to a lot of biomass. Cow-dung, -urine and small quantity of jaggery are fermented for three days to get what is known as Amrit Pani in Natu Eco farming. Then green and dry crushed biomass is pickled in the Amrit Pani for a day or two. The drained mass, crawling with soil animals is layered with a little earth, wood ash from cooking and piled 1 foot high. In 45 days, this turns into sweet smelling nursery soil or Masala Mitti in Natu Eco.

§ Productive root system of plants and trees are only 10" deep. The deeper and wider root system you find in nature are for anchoring the plant. So, if you propped a plant, a foot of enriched soil [or, Masala Mitti] is enough. The plant produces physical material from sunlight and atmospheric carbon and nitrogen; only micro-nutrients are sought from the soil.

§ For optimum photosynthetic efficiency of plants and trees, luxurious canopies are unnecessary and only increase transpiration. Careful attention is paid to canopy management by considered trimming and pruning.

§ Per square foot of Natu Eco farm, only one litre of water is required for ten days. For 10-G or 10,000 sq.ft, water requirement is only 1,000 lpd. This can be harvested from rain, supplemented by intensive recycling of all gray water.

§ Apart from the initial setting-up cost, a Natu Eco farmer needs no cash to buy anyhing from outside. He can produce all grains, vegetables, fruits, herbs, oilseeds and fuel wood for a family of five and have surpluses to generate a small cash income.

The 10-G plot designed by Deepak Suchde at Panvel, draws from Permaculture for lay-out, and adheres to Dabholkar's ideas in practice. Tall trees are planted along the edge, where a hedge of Vettiver prevents run-off of top soil. The !0-G are divided as follows: 1 G each for a family homestead; for workshop and stores; for cattle and chicken; for fruit trees; for paddy and other grains; for a nursery; for water storage; for cotton and fibres; for fast growing fuel wood. Half Guntha each are reserved for spices and oil seeds.

The pilot at Panvel is just over a year old and already fruit and vegetables are regularly produced. The first attempt at growing rice was washed away by heavy rains. Paddy has been sown again. The entire soil was close to lateritic. Judiciously placed Masala Mitti piles are the bed on which all plants grow. No electricity is used. All watering is by hand. Even for paddy.

Deepak Suchde has just started to develop a large parcel of land in Madhya Pradesh. He is available as a professional Natu Eco consultation. He can be contacted over his mobile [0-94224-43390] or email [deepak_suchde@rediffmail.com]. Dabholkar's definitive book 'Plenty For All' is available from Suchde, for Rs.450 each [-which includes postage within India]. Video CDs on the 10-G project are also available from him. Enquire for prices.

Firm focus:

Amidst all this, the steady passion for 'total change' has not dimmed in G.G.. He has said elsewhere:

"We have come to the conclusion that constructive work of a million-plus voluntary organisations, which have two-crore workers and mobilise nearly Rs.1,800 crores annually, has not changed society; it has only applied some balm to the poor and to some extent done what the state should do. In a sense, this has only prevented the sensitive and idealistic youth from doing some basic work. Reflecting on this, the Meherally Centre came to realise that if sangharsh [struggle] is combined with rachna [creative thought], basic changes will occur.

"During the freedom movement people accepted many new values much more easily and the same happened during the JP movement. Hence there is a need for sangharsh with rachna to effect basic changes in society. In view of this, the centre established the Yusuf Meherally Biradari to promote communal harmony and fight injustice."

The inevitable hard journey then began. News of such a development naturally evokes both hyperbole and skepticism. Media picked up the story and all Nagpur was agog. Then on Sep 2, 2003, the Union petroleum ministry sent a team from Indian Oil Corporation's [IOC] R&D department.

They were dedicated investigators. They sat all day in Alka's lab, even taking lunch there. They measured and noted everything, peered into corners and took away samples they produced with their own hands. Then at the invitation of the minister Ram Naik, another demo took place at IOC's Faridabad centre. Two more demos followed in Mumbai and Delhi.

IOC then declared its findings in a report: "The products have been tested at IOC R&D and recommended possible end uses are as follows: For liquid hydrocarbon: agricultural pumps, DG sets, boiler fuel, marine bunker fuel, as input for petroleum refineries, fuel oil etc; For gas: any nearby industries using LPG, in-house consumption; For solid fuel: thermal power plants, metallurgical industries." The minister then declared a grant of Rs.6 crores for a pilot production plant to be set up by Zadgaonkars in collaboration with IOC.

The freedom run:

Only, the grant never materialized. Alka and Umesh wrote letters, reminders and called. Things stayed intriguingly silent. When they probed deeper they discovered that a senior science bureaucrat was angling for equity in the venture. Elsewhere, Alka's PhD guide was campaigning to be named co-inventor.

Well, well what's new you say. Aren't these typical of India. Yes, odds are indeed stacked against those with novel ideas and spontaneous help seldom comes forth. But aren't heroes meant to be of sterner stuff? And if there weren't enough of them around GoodNewsIndia can't have run for over five years. A hero does suffer setbacks but they don't stop him. Nor does he make a display of his martyrdom. A hero vaults the odds or works around them.

In 2004, Umesh, ever the entrepreneur, flushed the whole connection with IOC. He went over to the State Bank of India and presented a business plan. They were interested but would conduct their own trials on the idea. It was soon done and a team of senior bank staff arrived in Nagpur to grant a loan of Rs 5 crores. Alka's patent was treated as equity and pledged to the bank as security. In under six months the plant came up and in 2005 production began.

The rest we know.

Umesh is a busy man now, taking calls and meeting potential franchisees. A delegation of Chief Ministers from five states have visited to explore setting up plants in their states. A team from Netherlands is in dialogue to see if the produce can be mostly solid coke instead of liquid fuel. A team in IIT, Mumbai is designing automation features for standard 5 TPD units to be set up by franchisees. But these are early days still.

For now, clients in Butibori Estate's industrial units are buying all that Unique can produce. The Bank has seen repayments begin. But at the Zadgaonkar household, values have hardly changed. Success sits lightly on this family of knowledge seekers: Alka refuses to give up her calling as a teacher.

______________

Prof [Mrs] Alka Zadgaonkar

Head of the Dept.- Applied Chemistry,

G H Raisoni College of Engineering, Nagpur - 440016

Phones: Home: [0712] 2220111; Mobile: 093701-20111 [Umesh Zadgaonkar];

email: auzchem@yahoo.com; umeshz@yahoo.com

February, 2006

People are the best capital:

In 1987, the first counter-attack began. Funded by the Ford Foundation, Anna University in Chennai began a study of sustainable schemes for water security. They discovered the obvious: that without recharging villages' water bodies with rain water, capital assets like pumps and irrigation systems have no meaning. Vasi was consulted for his knowledge of villages' social structures, in order to organise people in water harvesting. That was a major turning point. He had been a farm child and yet, it had taken him 32 years to look past 'modern' education to understand sustainable living. [Urban Indians can be forgiven if they take longer. Only, one hopes time will be on their side.]

His eyes began to see villages differently. His ceaseless proposals-writing and fund raising had scaled from Rs.1 crore to Rs.30 crores in his five years with ASSeFa. This had been poured sincerely into villages with no leakages. Yet, from sustainability point of view there were few successes. Most initiatives needed constant re-funding.

PRADAN then became convinced that professionals must themselves become innovators in development and not remain mere managers. Vasi ended his deputation to ASSEFA and returned to PRADAN.

In 1990, PRADAN conceived the Kalanjiam idea ['granary', in Tamil]. It was a micro-finance initiative for women and it became, after two years of field work for an initial breakthrough, a runaway success. Simultaneously, he set up a team to start work on the traditional water bodies at Madurai. In 1992 he took over as the Executive Director of PRADAN and the head office shifted to Madurai. The next five years took him all over the rural heartland of North India in Bihar, Orissa, Rajasthan, West Bengal etc to consolidate, strengthen and broaden the scope and depth of the work of PRADAN.

PRADAN was created to 'build people to build more people'. Ideas must be conceived, tested, proven and then scaled to become well-oiled systems- and then left to people themselves to manage. In keeping with that thinking, PRADAN thought it fit to spin off DHAN, by 1997 with Vasimalai as its Executive Director.

After proving the workability of thrift groups managed by barely literate women, DHAN began to scale up Kalanjiam. Avoiding a pyramid, they kept federating small sized self-help groups [SHG]. These autonomous federations are affiliated to DHAN for mutual consultation and idea generation. Soon the Kalanjaiam movement was self-reliant enough to be spun off from DHAN; the Kalanjiam Foundation [KF] is today an autonomous body in the DHAN Collective.

And now, Micro-Insurance:

Mayiladumparai- what a lovely name! In Tamil, it translates as 'rock on which peacocks dance'. But when the first Kalanajiam began there 1994, it was a remote block of Theni District which was sinking in poverty. Men took to drink or buses to nearby Kerala. Young children were sent away to far Andhra to work and feed themselves. Once a wooded country, over-grazing had turned it into near desert. Usurers completed the ravaged scene.

Today, the Kalanjiam Federation there -Kadamalai Kalanjia Vattara Sangam [KKVS]- consists of 270 Kalanjiams with over 4,000 women members in 81 villages. They have a saved capital of Rs.180 lakhs. That money -plus much larger leveraged loans through banks- has seeded many income generation activities.

Women there have turned out to be unstoppable innovators. In 1997, KKVS launched the first version of its life insurance scheme. For a premium of Rs.100 a year, a member and her husband ,if they were under 55 years, were covered for life and assured for Rs.10,000. The idea was an instant hit in an area where heath services are notorious. 1,000 members signed up.

By 2000, 1,500 members had signed up. KKVS now extended cover for hospitalization expenses, unless it was a chronic illness. Hospital expenses up to Rs.10,000, for the whole family including unmarried children, was covered under a premium of Rs.150.

There are insurance committees at local Kalanjiams and at the federation level. These are tough businesswomen. They tied up with a few hospitals in nearby Kadamalaikundu and Theni, after bargaining for the best deal. Patients are admitted without any advance payment, KKVS's credit worthiness being sound. Members also get a 20% discount.

For the intrepid innovators of KKVS, even this was not the end. In 2004, after working out the economics of their insurance as a business, they built a small hospital next to their office, and hired a full-time doctor: members can avail medical services using their membership cards and paying just 25% of the cost. And then they closed the circle: it is now mandatory for all members to join the insurance programme, if they were seeking credit from Kalanjiams.

In just four years, these nearly illiterate women have shown their innovation and management skills. Their books are audited internally and externally. The business has shown a surplus for every year since inception. Health and hygiene levels have risen, along with confidence levels. The entire programme was evolved by rural women, with an occasional nudge and input by DHAN.

They have driven big insurance companies out of town. In any case, pressured by the insurance regulator, IRDA, these companies were practicing tokenism, to claim they covered poor people as well. KKVS has made them redundant. No longer do people need to fill the papers that corporations want; nor do they need to beg their claims to be processed. Deaths or illnesses are verified by members for faking. Bills are settled immediately without elaborate paper processes. Significantly, all the premia stay within the local economy instead of gathering in some high-rise office in a far city.

Shock and awe in village India:

When MGM's AppleBash party began at 7.30 pm on July 31, the whole village shook and throbbed. We had heard nothing like it before. It was impossible to talk to someone 3 feet away in our homes. The Inspector of Police from Neelangarai came to meet a group of livid ECCO members. He was apologetic, even sheepish. He said he had told them to wind up by ten, asked us to bear up till then and left.

At 11.00 pm the decibel level had only risen. We decided that enough was enough. Sabita, Navaz and I began the half kilometer walk to the temple land, now a party venue. We walked on the beach, where fishermen whose workday begins at 3 am, sat jack-knifed in bewilderment, unable to sleep.

The old sacred grove was a green savanna, lit like a foot ball field. We walked in from the beach and waded through milling crowds. We counted 6 bars in the periphery doing brisk service. It was a party to launch MGM's vodka brand. Most of the guests were liquor vend workers in their several hundreds. They were lolling about, high on free samples. Two speaker towers, each 10 feet high were pounding the earth. An inane DJ was spinning music and urging folks to c'mon, have a good time. Many 'folks' instead were relieving their greedy bladders on the beach. Sabita was chatting up some young constables and noting down their names. She learnt they were on 'security detail' till 3.00 am.

I was soon spotted by MGM's Chief Operating Officer Mr Sharma.

"Sir, do you have an invitation? This is a private party," he said.

"Private party on public land? No I don't have an invitation. Since I can't sleep I have decided to take a walk to find out what's going on," I said.

"Throw him out," snarled Mr Sharma to his security staff.

I stood my ground and snarled back:"I dare you. If I am on your property call the police to throw me out. There are plenty of them here." I glowered for a while and walked deeper in, calling the DIG, SP and the Inspector on my mobile, the while. It was coming up midnight; the party was raging on.

Presently, I saw Mr M G M Anand. I walked over and greeted him and asked how come he was running a party on temple lands.

"I have a lease to these lands," he said.

"Show me and I will leave," I said deciding to call the bluff.

"Not now. Only during office hours," he said tartly.

"Very well. I will get in touch," I said. "Even if you do have rights to this land you are violating noise control laws of TNPCB."

He turned to COO Sharma and said, "Ignore him. He is an extortionist. He is here looking for some money."

And I said: "Mr Anand, money is the only thing you know and deal with. I'll show you a few more things about life before I am done."

The Timbaktu mission:

In January,'89 Mary and Bablu got married. In November that year Mary, John and Bablu pooled their funds to buy 32 acres of derelict land. They called it Timbaktu, for want of a better name [-was there one?]. 'This we shall green', they told themselves. As it always happens at moments of such resolves, wise counsels descended upon them. Mollison, Fukuoka, watershed development and afforestation were their new drivers.

Timbaktu will be a commune devoted to nature. It will seek to attract individuals who believe in the primacy of nature. They will live without the frills of life but with the most commitment to enable nature to regain a foothold. They had little money but a clear vision. But they had resourceful people like Simhachalam and his wife Sashi. These two had been Mary's comrades in Srikakulam and moved in with her to Timbaktu. Bablu says, "Without these two, who are of rural stock, we would not have dared to start Timbaktu, let alone live on it,"

The 32 acres lie almost two kilometers from the highway. No road to it existed and only an informal one does, now. Electricity is not available. Around it are several hundred acres of barren wilderness. There were hills in the backdrop that had been denuded. Between recurring droughts, need for firewood, and the local cattle that graze them to a close clip, the hills had no chance.

Land as teacher:

"First thing that happened was that we began to lose our arrogance, because the land dared and mocked us," says Bablu. They realised they must cooperate with people to get anything done- lectures won't do.

The land they had bought had been a meeting place for herdsmen. Instead of fencing its property in, Timbaktu began friendships with them. Mostly they exchanged stories and in the process gained a lot of local lore.

It is not as though the poor in India are unaware of the need to care for nature[Not so, the well-to-do, though]. But they need solutions for living out their daily lives; work for any distant goal had to be fitted within their tight time-table. Over months, there was an accord on some measure of cattle control. With that agreed, nature got its break. The hills began to regenerate and trees began to display their crowns.

There were results to see in just one year. In the protected areas grass production shot up. They could send away cartloads of grass. Next year they managed to get over 700 acres of hill sides under grazing control. Herdsmen were drawn in further and taught fire-patrol, prevention and fighting. Everything was kept informal and corrected as and when needed. Timbaktu's own acres however were planted with greater design, the Permaculture way.

If these two requirements are not met, the Mandal withdraws all support to the school. These conditions motivate teachers, headmaster and the whole village community to monitor and support the child, lest the whole school should forfeit assistance. The support funds are deposited in a local bank account jointly operated by the headmaster and the student.

So affordable for us:

It costs a mere Rs 2,000 per year to support a child's entire education. To take a child from early education, through to a three-year bachelor's degree in college, it costs but Rs 30,000 spread over ten years. The Mandal has never approached the government for help, because it works on the basis of caste. Supporters have not been lacking. Early donors were Mandal members. Soon doctors in Nair Hospital where many Mandal members are clerks, adopted several children. Others followed. As of date, the Mandal has arranged totally supported education of 171 children, 91 of them girls.

Most of the Rs 500,000 they raise annually for purchases, comes from members' own contributions and their friends'. They never run active campaigns or approach any firms. Pawar firmly believes the middle-classes must take to philanthropy. "There is a belief in India that philanthropy is for the rich," he says. "We want to show that everyone can afford it."

His faith has not been belied. Most of the funds are from faces in the street, offices and trains.

Once every two years, they stage a Marathi play as a fund-raiser, the proceeds from which are considerable. They bring out a souvenir volume on the occasion, featuring articles by members, teachers and beneficiary students. Details of Mandal's activities are included.

Whenever there is a short-fall, a member takes a personal loan for a year, to be repaid from Mandal's proceeds next year;this goes on by rotation. "There is no lack of money for good causes," says Pawar.

In delivery mode:

When the shopping has been done, it's time to plan the trip to deliver the goods to the schools. The Mandal has a well ordered structure. Besides the President, 3 VPs and a General Secretary [Pawar], there is an Executive Committee of 19 members. No one is ever paid anything, not even incidental expenses. The Mandal has zero-overheads. What they raise equals what they give. All incidental expenses are picked up by member subscriptions.

Arvind muses: "The bureaucracy succeeds by tiring you, hoping that you will give up. Often we do. If at first we don't succeed, we wilt and blame the system. We must learn to fight in the courts, the offices and streets". Parivartan filed a public interest litigation seeking direction to the department that it implement a 5-point transparency programme.

By now their ranks had swelled. They had a rudimentary office with a phone. Manish Sisodia, a journalist with Zee News got the media to cover Parivartan's campaign. The Commissioner finally, reluctantly filed an affidavit in the court saying that an internal order had been passed along the suggested lines.

Kejriwal the mole, knew it was a lie. There was no such order. On 3rd July 2001, thirty volunteers of Parivartan sat in a peaceful satyagraha in the corridor outside the Chief Commissioner's office, seeking a copy of the order he had sworn to have issued. Pressured, he met them, made vague promises and sought a little more time. Finally, under threat of a larger group of volunteers offering satayagraha with full media in attendance, the Chief Commissioner was broken.

Lessons learnt:

On the July 13, orders were issued to departmental heads. By Jan 18,2002 most of the suggestions had been implemented. Parivartan had scored a success, albeit a small one for which so much time and energy had to be expended. But that's the Indian reality. Out of such small battles are systems in a democracy reformed, inch by inch.

By now the Arvind Kejriwal had unmasked himself. He has since used every provision of the service rules to go on long leaves in order to work openly for Parivartan. He has been without a salary for three years now, running his family on his wife's earnings.

Parivartan has a free-wheeling structure. It is not an NGO nor a body registered with any authority. It is a mere Association of Persons, the loosest form permitted by law. It does not accept corporate funds, let alone foreign ones. Kejriwal says there are private donors for their costs. [Still, GoodNewsIndia would urge readers to extend their support.]

It has a small core team of four modestly paid workers, most of them residents of Sundernagari and Seemapuri slums. Rekha Kohli, 26 is the publicist. Chander is the original phone boy, now looking after the office. Rajiv Sharma, 30 is a master strategist plotting campaigns. And finally there is 21 year old Santosh, a product of the slums, a great street organiser and campaigner for rights. They decide on the salaries they will take, beneath a ceiling of Rs 6000 per month.

The team realised how hard and long battles can be and the results so minuscule. Unless there was a campaign for fundamental, systemic change to make the bureaucracy more easily accountable, citizens will always weary and give up.

Self-help for water has become a major civic activity in Chennai. Temple tanks,those munificences of wise old kings, are being spruced up in Chennai. The Rotary Club helped revive the Kasi Viswanathan temple tank in Aynavaram. The state has desilted and repaired tanks at the Kapaleeswarar and Parthasarathy Perumal temples. But possibly the finest example of people's action is the revival of the 5.5 acre Surya Amman temple tank at Pammal. Mangalam Balasubramanian, an adviser for Danida, has galvanised citizens and local businesses to raise Rs.12 lakhs to restore the splendid tank. Pammal has tasted success and keeps on doing more.

From waste to gray:

Currently in Chennai, water recycling is the big new buzz. Residents are cleaning up and reusing wash waterin toilets and gardens. Alacrity Foundations, one of Chennai's most conscientious builders who installed RWH systems long before the ordinance was issued, is now installing systems to recycle grey water. They believe, over 80% of the water that flows into the sewage can be reused. Hearteningly, there is a steady flow of recycling success stories in Chennai.

Chennai Petroleum, a large refinery and a heavy consumer of water has pioneered an exemplary recycling model. It actually pays Chennai municipal corporation Rs 8 per kilo litre of sewage. After letting it settle in holding tanks, it uses reverse osmosis to filter out solids. The resulting water is 98.8% and good enough to be used as process water. The sludge is let into vermicompost beds to produce manure that is used to maintain the vast campus, lush and green. The scale of operation is enormous: 1,500,000 litres an hour or 40% of the refinery's needs. It's a win-win solution for the city, the business and the environment. The project has generated great interest among other industries.

Sulabh innovated and improved the Gandhi idea, endorsed by WHO. Pathak's major contribution may well be that he realised that the pit privy was suitable for not just rural areas but for urban India also. A deeply sloping toilet pan was developed to enable effective flushing with just a mug of water. There was a double reward in that: water was conserved and there was no excess water to leach and pollute ground water. A standard, two pits and a toilet-pan, connected by a Y-channel was developed, which enables quick switch soon as one pit filled, after say 6 months. [To view a typical plan, click here and for a sectional view click here] Many variations of the Pan-Y-Two concept were developed to suit local conditions.

And then Das and Pathak sat and waited for a break that would help them take their solution to the world out there.

Rendezvous at Arrah:

The break never came. After a three year wait, Pathak with a family to feed, went back to selling grandpa's home-cure bottles. But the Sulabh obsession never left him. Walking the streets with a 15 kg load of bottles slung on his shoulders and an arm, he rued the five years in Patna chasing government help.

In the small town of Arrah, Bihar, the break finally came. Noticing a tiny sign that read, 'Municipal Officer', Pathak walked in and began to retail the Sulabh idea. He had an order within minutes. The officer was an enthusiastic convert and at once advanced the princely sum of Rs.500 for two public toilets. Thus it came about that India's first two-pit, maintenance-free privy was built in Arrah in 1973 by Pathak using local masons.

From Arrah also, emerged the Sulabh business model, that holds good till this day: Sulabh will insist on advance payments but will seek no subsidies, donations, loans or grants. Orders followed in quick succession and soon made the entire Sulabh operation self-sustaining.

Bhima Sanghas began to sprout everywhere in Karnataka. Each is an informal club where working and school-going children gather and exchange notes. Damu then began to ask local panchayats to allow children to attend their proceedings-- and that was the beginning of Makkala Panchayat [Children's Panchayat]

Children activists:

What a dramatic difference that has made! Children have brought new perspectives and ideas to decision making processes. There are any number of heartwarming examples of children's activism. Here is a small selection:

◊12 year old Rehman could not bear seeing his 'sister' being teased by adult louts. She was a domestic worker. Rehman roused his Bhima Sangha members to stand up to the bullies and have them jailed for 10 days.

◊Uchengamma, a 15 year old Dalit girl of Holagundi village, Bellary Dt. in Karanataka fought against her parents design to marry her off. Her Bhima Sangha rallied to her help, even smuggling her out of a locked room in her house and dramatising her plight through the media. Her success has led to six other child marriages being stopped.

◊Members of several Bhima Sanghas decided to meet the new Mayor of Bangalore and bring to his notice, problems that children face. They marched two kilometres through lanes in their neighbourhood carrying placards and singing songs. A 11 year old carried her two year old sister throughout the walkathon. The mayor sorted out many of their problems.

◊When the Konkan Railway was laid out, it ran through Nandanavana and Karikalli villages cutting off an important foot path through which children fetched firewood and ran errands. People had to make 10km detours daily. About 900 families were affected. Local Bhima Sangha swung into action and stood with protesting adults. It made individual representations and received a direct invitation from the authorities. Children met them and convinced them of the need for an alternate path. They got it.

◊Bhima Sangha members are great communicators. They run a magazine called Bhima Patrike, which has an apex editorial committee. Children also produce a wall newspaper. Bhima Kala Kendra is a children's theatre group that creates awareness about the environment, HIV/AIDS, communalism, plastic litter etc. They also narrowcast an audio magazine called Bhima Vahini, although it is currently off the air. Mainstream media uses a number of Bhima Sangha correspondents in villages to gather news.

◊In Nandroli hamlet of Keradi Panchayat, members of Bhima Sangha worked out the amount spent by the village on liquor, using a breathtakingly simple technique. They went to the liquor vend and cleared the litter of empty plastic sachets. They then waited all day and collected the new empties flung out of the shop. At Rs.11 per packet of arrack, the annual liquor spend came to Rs.12,00,000! Armed with this evidence the local Bhima Sangha confronted the adults, startling them into action. There has since been increasing control on arrack sales. The village panchayat is now working to make Nandroli liquor free.

Adjacent to his home is a small temple he has built for Guru Nanak to whom he is devoted. Often, there is a gathering at home of neighbours for a satsang or discussions. He has made his will, reduced his wants to a minimum and the clutter in his head to nothing. After all, he watches the TV for just two news bulletins from Doordarshan. He walks to most places, wears only khadi, and quietly states the importance of Gandhi. He is entitled to a freedom fighter's pension, but refuses to claim it saying he doesn't need it. He travels only second class, paying for it, though he is entitled to passes. He is a gritty old man.

His growing, admiring family worries about his hectic life. But it has no control over him. Dada is a bit of an eccentric tyrant, who will brook no delays or sloppiness. His nephew Sunil, now abroad, feels Dada's pull from afar. He explains: "I read in school about the Indian concept that we all bear three debts ["Ryn", in Hindi]: Matri [of Mother], Pitr [of Father] and Guru [of teacher]. To be truly free of these debts in your lifetime, you have to be one of the two: parent or teacher. I think Dada, a bachelor, takes commitment to others quite seriously, but without words or any consciousness."

That is all there is to the life of Dada Devkishan Lakhiani. No drama, no disciples, no teachings, no headlines, no expectations. Luckily for India, he is not unique. There are thousands like him keeping the society positively disposed towards the future. Look around you in your neighbourhood- you will probably find one.

These simpletons don't read detailed analyses, make speeches or rile against the ills around them. They doggedly do what they can. It is they who will enable the meek to inherit India.

______________

Devkishan Lakhiani

c/o Arvind Lakhiani

17/4, Navjivan Colony

Mori Road, Mumbai- 400016

Tel : 022-56662396, 98212 21216

email: sunil518@yahoo.co.uk [Dada's grand-nephew Sunil Lakhiani]

______________

This story was made possible by interviews, field reports research and photographs by Shruti Parthasarathy [ psarathys@yahoo.co.in ]

_________________

September, 2004

Bonding grew stronger. The Sarvodaya Maha Sangha, their federation, had by now an anthem for a robust sing along. Sneha Jatre, 'Fraternity Picnics' became an annual event. People come from all villages with cooked food and spent a whole day interacting and sharing each other's travails, dreams and food. They went out on excursions as well, with some amusing spin-offs.

From Anna Hazare's Ralegan Siddhi they brought back a 'mocking pole' and set it up in the middle of a troublesome village. Drunken wife-beaters were left tied to the pole for a whole night, to be mocked by children and passers by. "The pole soon became redundant," they laugh. Drunkenness is rare. Usury is dead.

Lifestyle changes:

Burgeoning savings with the Sanghas have seeded many small businesses. Close to 800 toilets have come up and most have linked them to their bio gas plants—a taboo just over decade ago. Awareness of hygiene, nutrition, education and family planning has increased.

B G Linganna Gowda has a nice business [-about Rs.20,000/month], buying surplus vermicompost with farmers and selling it elsewhere. He's a finicky buyer but also a good teacher. So, knowledge, quality and volumes have risen.

Villagers have become experts in water use and waste management. Mulching and in situ composting are routine. Over 600 families have kitchen gardens and 560 have smokeless stoves.—these numbers are growing. Silk worm farming is a new business. Villages in all, have 17,000 feet of lined waste water drainage.

Pakkeerappa had branded himself the village dhobi, keeping a low profile in the village. He had convinced himself that his 3 acre plot was useless. A pond changed all that. He lives on the land now and raises jowar, lentils and fruits. His vermicompost is premium grade, says Linganna.

Basappa was going to sell his 7.75 acres and move to the city as a labourer. He listened to BAIF and took to growing fruit trees. "I used to head to the city looking for jobs," he says. "I now employ people to work for me. After feeding my family well, I have a Rs.10,000 surplus every year."

"I can understand the plight of people without land to live on and grow their food. But I don't understand those with land, complaining, asking for the government to help. I am sorry to say this, but their problems can only be traced to two things: greed and or ignorance of how nature works. Often, the latter. They are led astray by fertiliser, seed and pesticide companies, bore well contractors and politicians who say, I will give this free and that on credit. We have farmers seduced by exotic crops and huge profits. All in quick time. They are finally led to suicide."

Ramachandra Rao has nothing more to say. He is clearly upset.

Cherkady changes too:

Rao's elder son returned to Cherkady after retiring from the bank. He declares he's happy to be back. He has built himself a substantial house in a corner of the land. Electricity arrived two years ago. The old man suffers it albeit with some grudging concessions to its merits. There's also a small electric pump drawing water from the well.

The Gandhi toilet has fallen out of favour. "It needed just one mug of water per use," wails the old man. Alas, rice grows no more: the trees are so big and everywhere, that hardly any sunlight falls on the land. So they buy rice to eat. But Rao has preserved his success species. Elsewhere in the state, there seem many people who want to know how to survive on heartache-land. Rao travels frequently to teach his secrets.

The drive back to Brahmavar, suggests a new interpretation of the story of Eden, as possibly told by Brahma: Nature decreed that for those without greed, there is enough to live happily by. But man wanted more. He looked up from the soil and gazed into the distance. And, was tempted by chemicals, credit and fork-tongued promises. He was drawn away from the land and began to wander in confusion. Soon he was lost, and often killed himself. "The original sin", said Brahma, "is greed."

Back on the highway by the sea, leaving Brahmavar behind, the road ahead somehow seems littered with doubts.

_________

For those interested in natural or organic farming, the life and work of Masanobu Fukuoka is essential reading. Here's is a useful link. The Fukuoka Farming Website

_________

Cherkady Ramachandra Rao

Khadi Dhama,

Post: Cherkady

Via: Brahmavar, Udupi District - 576215

Karnataka

Phone at Mr Rao's elder son's home: 08252-569299

July,2004

Rights in a left world: An Indian used to routinely being lectured on his country's rights-record in Kashmir, in Gujarat, towards minorities; his treatment of the lower castes, the poor, women, children; his presumed natural tendency to deceit and bribery, and even, his 'racism' in not enthusiastically accepting a foreigner as his prime minister... for such an Indian, the ability of the Chinese to brazen out all external criticism must be an object of envy.

For, China has proven that it is possible to do so and get away with it. For 3 weeks in 1989, civilians—mostly students— gathered in Beijing's Tienanmen Square in protest against a wide variety of social issues. The state moved with alacrity. The details of what happened may be read here, but at the end of it, 2600 lay dead and over 7000 were injured. It was thought that the West would break-off with China on the issue. 15 years down the line the West is an ardent admirer and, London's Economist says "organised dissidence is non-existent". And adds, that many of the survivors are successful capitalists today.

In Kashmir, no 'outsider'—even if he is married to a Kashmiri girl—may buy property under a covenant known as Article 370. In just forty years, China has overwhelmed locals in Tibet by a planned influx of ethnic Chinese.

Charles Horner, a Senior Fellow at the Hudson Institute, Washington D C, in a brief and sober history of Christianity in China says that "it is hard to appreciate the scale of the American Protestant effort in China from, say, 1850 until the establishment of the Communist regime in 1949. But it was huge, and drew upon the energies and the funds of Americans in every part of the country. It built schools, universities, and research institutions as well as churches" . Despite that, the harvest of souls, has been poor. The official number of Christians in China is 10 million though very greater number, is said to be covert practitioners. The Pope has applauded them for "not [giving] in to a church that corresponds neither to the will of Christ, nor to the Catholic faith". China's 4 million Muslims have largely subsumed their religious identity within a national one. Clearly, in China only the state has the sole rights to social engineering.

Significantly, Horner adds, "Chinese Catholics are unusually prominent in the ongoing struggle for democratic rights". And that leads us to an understanding of the Chinese mind. Sun Yat Sen and Chiang Kai Sheik were deeply distrusted by nationalists [-who later mutated as communists] due to their Christian faith. That distrust of democracy as being an instrument of the Christian West continues. What chance then, does Falun Gong stand? You will find its clone in every Indian district, promising peace and health. In China, it is feared as a proselytiser that will upset political power.

Even as one wall was coming up hill, down in the plains, another was about to be brought down. The Rishi Valley School is an expensive place for most Indians. It does produce very sensitive, free spirits but an invisible cost wall does run around it. JK had started a school for rural children in a 14 acre campus nearby but it had remained a place without much energy. In the eighties, even as the hills were regenerating behind a wall, Radhika Herzberger had taken over as the Director of the School. She is a scholar in Sanskrit and Indian studies. More importantly, owing greatly to her mother Pupul Jayakar's devotion to JK, Radhika had a proximity to JK which enabled her to internalise his vision. Radhika realised the need for making quality education available at the primary level everywhere. And that is how the Raos arrived in the valley.

Arrivals:

Y A Padmanabha Rao and Rama [-pronounced closer to Ramaa than Raama] are both in their early forties. They met while at university in Hyderabad and discovered they were both looking for something they couldn't define. They were certain though, that conventional careers were not for them. What drew them together was their search for a worthwhile mission. They got married and went away to a village to try their hands at farming.

"Sidhipet didn't turn us into great farmers," smiles Rama. "But we found out what we wanted to do with our lives. Local girls, poor tribals would come up to me and seek one invariable favour: "teach me"! It struck me how the poor valued education ahead of even money." They soon came upon an advertisement seeking teachers -- in the rural school at Rishi Valley. Their mission awaited them.

But before we trace that, let us take note of something that seemed astir in Rishi Valley in the mid and later 1980s. Was it the emergence of nature's ecosystem or was it the collective unconsciousness of kindred spirits? In Chennai, V Shantaram, a chartered accountant in his late twenties, walked out of a secure career path to enrol in the Salim Ali School in Pondicherry to study ecology. He became an ardent ornithologist, his study of woodpeckers earning him a doctorate in 1989. He arrived at Rishi Valley to teach. Dr Ajith Gite had came over to be the School doctor. His wife Nalini hailed from Pune, but had spent her youth among tribals in the Dang district of Gujarat. She was an Ayurvedic doctor qualified at the Aryangla Medical College, Satara but says she learnt her pharmacopoeia from an Awary tribal chief in the Dang jungle. Ajith was a workaholic and died at the School in 2002. Nalini is creating a comprehensive herbal conservatory now. M S Sailendran is another chartered accountant seduced by nature. He came to the School as an internal auditor and stayed on. He is the School Bursar and a keen conservationist. Jayant Tengshe graduated from the prestigious IIT, Powaii. Instead of riding the conveyor belt to Silicon Valley, he surrendered to the gravitational pull of Rishi Valley. He teaches mathematics and works with Nalini in increasing the diversity of her collection. More recently young medical doctors Dr Kartik Kalyanram and his wife Dr Vidya Kartik have settled here to build the Rural Health Centre. Let us meet them briefly for now and move on. Their individual lives and works, as we shall soon see, will synergise and lock together with precision.

Bernie and Greg continued their dialogue. Perhaps their disillusionment was because they were either working within restrictive confines or against insurmountable odds. That need not imply there was no meaningful, selfless service required by people out there. Perhaps too, they must identify small groups of people and help them rise, without fancying themselves as God's or Nature's sole missionaries. They perhaps had to redefine their lives' goals. They spent hours talking. They explored Vipassana meditation. They married in 1993 and decided to move to Greg's ancestral home near Margao in Goa. They had no work plan.

Bernie and Greg continued their dialogue. Perhaps their disillusionment was because they were either working within restrictive confines or against insurmountable odds. That need not imply there was no meaningful, selfless service required by people out there. Perhaps too, they must identify small groups of people and help them rise, without fancying themselves as God's or Nature's sole missionaries. They perhaps had to redefine their lives' goals. They spent hours talking. They explored Vipassana meditation. They married in 1993 and decided to move to Greg's ancestral home near Margao in Goa. They had no work plan.

In 1997 -- four years after their arrival in Margao, Goa--, Jan Ugahi was registered as a charitable trust. Student volunteers from colleges began to drop by. Greg returned to his passion-- giving tuitions. And Bernie to hers-- standing up for rights. They went on picnics, staged plays, held sports meets, celebrated festivals, sang, danced and cooked and ate. People came over from other slums in Saddu Bandh, Malbhat, Aquem Bandh and Santan Chawl.

A 'Childline' was set up to handle calls related to offences against children. Jan Ugahi volunteers began to man it. On March 19, 2001 Bernie manning the Childline, heard her nagging worry coming true as a nightmare. She dragged the police to arrest 71 year old Briton, Middleton Colin John at a guest house in Benaulim. He had two Nepalese boys in his bedroom. He was charged with paedophilia related offences. Elsewhere on the same day, a 63 year old Goan, Lawrence Fernandes was arrested on similar charges. Goa was rudely waken up to the reality of child abuse that the new affluence was bringing.

Nippon Steel in Japan, "aims to achieve a 10% reduction in energy consumption from the 1990 level by 2010 and an additional 1.5% reduction through the use of waste plastics." Its process is run captively and rather more involved than the Garthe method. "In the coking chambers of the coke oven, the waste plastics are heated to about 1,200 Deg.C in an oxygen-free condition and pyrolyzed. The charged plastics are pyrolyzed at 200 Deg.C to 450 Deg.C, generate high-temperature gas, and are completely carbonized at 500 Deg.C. Hydrocarbon oils and coke-oven gas are refined from the high temperature gas generated by pyrolysis, and the residue is recovered as coke." You can read the details in this illustrated PDF file [jump to pages 16 and 17]. \

Markets for Plastofuel nuggets in India will however be at the lower end. Already, waste plastic admixture with bitumen is well proven. Plastofuel nuggets may also be used in many industries --small and large-- to generate process heat, using suitable burners.

A road-map for India:

With proven technology and markets available, India needs but a few crucial interventions to turn plastic menace into an opportunity. GoodNewsIndia believes, the following initiatives are needed:

§Incentivise and mandate, village and city governments to gainfully employ locals to gather *all* plastic waste, at as few designated points as possible

§Incentivise and motivate, cottage level entrepreneurs to turn the waste into PDF nuggets or transport to the nearest nuggeting plant

§Mandate road laying contractors to use nuggets as extensively as feasible

§Incentivise the use of PDF by hotels, hospitals and process industries for their heat requirements.

Will that checklist do the trick? Not quite. There will be cost-gaps to be filled up, before the whole recycling idea will scale up, spread wide and pay for itself. And those gaps will have to be filled by the plastics industry in the form of a cess. After all, they enjoy a vast, prone market and it cannot be that their responsibility ceases at their gates.

Shristi struggles for funds because it won't cut corners-- it implements the 'best practices' in autism care. There is one teacher for four wards, an unusually good ratio in India. Their budget covers cost of transportation, lunch, medical care, nutrition, picnics, art courses and materials, sports, cultural events and festivals and orientation visits for their wards to parks, museums, post office, bank,restaurant, hospitals, shops... the list is endless.

Paying off:

Results are beginning to show. Parents feel more positive about their strange children. A sensitive name coined for this affliction is, 'Ooops... Wrong Planet Syndrome'. Indeed these children seem to have wandered here by mistake, and are bewildered unless we reach out to comfort them.

And the only way we can reach their soul is by love and patience. If we are sincere in trying to discover what they really like doing --for there are many things they enjoy doing-- and lead them to what among those are productive for them --and there are many things, they can be good at--, we may then make them feel at home on this planet.

It is through care and love that Shristi has enabled many children to live in peace and with some sense of identity. For example, Bhushan Balakrishna minds his family gift-shop by himself. Many other children have learnt to fend for themselves easing the load off their parents. About fifteen of them earn modest incomes from their craft-work and strut home proudly to their mothers with money in their fists. As for Hemal Avalani, that first arrival at Shristi, he is 23 years old now, and a faint shadow of the totally dependant young man. He commutes by public transport to his father's friend's business where he is employed. He can handle email, do his shopping and select music for himself. Above all, Hemal regularly saves a part of his salary and brings it over to Shristi every month to donate.

Hemals will ensure Shristi will endure. Wouldn't you too?

_________

All donations to Shristi Special Academy are exempt under Section 80[G] of the Indian Income Tax Act 1961.

_________

Shristi Special Academy

MIG 71, 1st Cross, V Main,

KHB Colony- Stage 2

Basaveshwara Nagara, Bangalore-560079

Phone: 91-080- 3204875

eMail: info@shristi-special-academy.org

Website:shristi-special-academy.org

Jan, 2004

Coming from the centre:

Fuad Lokhandwala's life has run a zig zag course. Born affluent, he grew up lonely and determined to make it on his own. "My marriage to Mehru was the turning point in my life. She was 18 and I, 20. Through her I came to know --and to deeply admire-- her family, especially her father, R H Chisti, IAS. He was by inclination a saintly man. That he was a direct descendant of the Khwaja, Moinuddin Chisti of Ajmer probably explains that. Through Mehru too I have Sanaa, my daughter and my passion. And now I have this mission. I ascribe all I have achieved to Mehru," he says dreamily.

An affluent man, a happy, family man, Fuad could have done tens of other things with his time. But India got lucky because Jay Leno made smoke come out of Fuad's ears. By the way, was that why he called his company Fumes? "Naaw," he drawls with a wink. "It stands for FUad, MEhru and Sanaa."

_____________

Fuad Lokhandwala, Fumes International

67 Anand Lok, New Delhi 110049

fumes_international@hotmail.com

Phones:91 11 2626 4661

_________________

This story would not have been possible without the contributions of Anuradha Bakshi. She interviewed Fuad, visited the toilets, took the pictures, sent the notes and handled all subsequent queries.

November, 2003

Despite all these assets at the back, what matters most in the markets is the 'front end'. Here India is blessed with millions of her children spread all over the world. They study hard, work hard, do science, teach, manage huge corporations, smile a lot, are polite neighbours, don't sponge on the state, write great books in English, sing, dance, win beauty contests, love their children and respect their parents. And they seldom make bombs. It is natural that the country they come from evokes curiosity. And the products and services from there are well received.

Now to the favourites:

It is a comment on the times that success stories from the IT sector which first put India in orbit, should be listed last. Not because they are losing their edge; they are thriving, thank you. But what is happening is that India is not just IT alone, anymore. There are salients in other sectors as well.

But knowledge-centred India reigns supreme. Just three years ago the Indian IT industry was the equivalent of garment industry's sweat shops, littered with phrases like data entry, Y2K and bodyshopping. About then, India began to do 'medical transcriptions' for US doctors. In a few months India had scaled up, met deadlines and turned in quality work. The world woke up to the opportunities that awaited in India. Soon 'call centres' popped up. The next link in the value chain was business process outsourcing [BPO]. Airlines, insurance companies, auto majors, World Bank etc began to shift their entire back office work to India and have these services delivered over the wire by an army of dedicated, intelligent young Indians. Infosys says that the 'offshoring' model has proven itself beyond all doubts.

Gartner Research says that five Indian software companies have the most mindshare among nearly 200 top corporations when they think of outsourcing. Sophisticated jobs are being shipped to India: financial and market analysis for Wall Street, for instance. So many jobs are leaving the West that there is resentment building up. Far from bragging their deals, Indian companies have gone mute. 'Business Line' headlined in July, 2003: "Fallout of outsourcing backlash - IT services firms keep client wins under wraps." After all, has not New Jersey passed legislation --never mind, all that stuff about free trade-- to stop jobs going to India? But not everyone is discreet about India. Morgan Stanley and Nasscom - McKinsey have predicted that by 2010, India's BPO revenue will be $65 billion and fueled by that,India will be a trillion dollar economy. And ruining it all somewhat further for India's comfort, Andrew Grove has just said, that India's booming software industry, which is increasingly doing work for US companies, could surpass America in software and tech-service jobs by 2010. "He warned that America's software and service industries, strong drivers of US economic growth for nearly two decades, show signs of emulating the struggles of the US steel and semiconductor industries."

In under three years Project Why's personal attention has changed all that. In the recent school examinations, pass percentage among the Project Why children was 98%. More and more parents are bringing their children over and more neighbourhoods are asking Project Why to start branches there. At Giri Nagar there is a PTA, an Annual Day, street sports, cultural programmes, picnics and above all dollops of cheer and hope.

More than a Centre:

Main Street Giri Nagar throbs with energy radiating from Project Why offices. Loud sing alongs of children, people bustling about purposefully and neighbours pitching in to help are everyday happenings. But early days were not so. Anuradha faced surliness and deep distrust. She was evicted from a park where she used to hold classes, driven out by shack-owners and even openly abused. But she has stood her ground and won the neighbourhood over. 'Lala' Baburam now a mild mannered employee running the crafts shop, says he thought Anuradha was seeking religious conversions. Many others like him greet her warmly today.

She calls Rani --a Giri Nagar local-- her 'executive assistant'. Rani takes care of the roster, time tables and very frequently, finding a home that would host a class in a hurry. There are constant improvisations to survive and run the classes. Rani says cheerfully, "Majboori ka naam Mahatma Gandhi!" ["When you face an obstacle, invoke Mahatma Gandhi"]. Bernie handles the external world: donors, visitors and the correspondence. Young Shamika is happiest caring for children with debilities and teaching English to eager eyed classes.

Money is of course a constant worry as Anuradha must spring Rs.85,000 every month. Whenever she is short --which is often-- she dips into her inheritance. But she says it's worth it and very satisfying. It sure must be, for she seldom dismisses a problem as not being hers.

For example, a small tribe of Gadiya Lohars have lived for close to fifty years on Kalkaji Road foot-paths. They are registered voters, have ration cards and yet are regularly hounded by petty municipal officials. Anuradha speaks up for their rights: "They are such a handsome, gentle people. They are itinerant blacksmiths. They used to follow armies in their exquisitely carved carts --'gadiyas'-- and service the arms and the horseshoes. Now they are treated as undesirables. They have a right to existence." When three year old Utpal's indifferent mother ignored his safety, the poor boy fell into boiling curry and sustained third degree burns. Project Why jumped in, treated Utpal and nursed him back to his smiling ways again. There is young Hussain a runaway from Bihar, who began as a floor sweeper at a computer company, got interested and has mastered enough to teach computers to others. Two young children went missing one evening and were found dead in a drain.

Approaches to the source:

Lakshmi Thathachar's view of Sanskrit's nature may be paraphrased as follows: All modern languages have etymological roots in classical languages. And some say all Indo-European languages are rooted in Sanskrit, but let us not get lost in that debate. Words in Sanskrit are instances of pre-defined classes, a concept that drives object oriented programming [OOP] today. For example, in English 'cow' is a just a sound assigned to mean a particular animal. But if you drill down the word 'gau' --Sanskrit for 'cow'-- you will arrive at a broad class 'gam' which means 'to move. From these derive 'gamanam', 'gatih' etc which are variations of 'movement'. All words have this OOP approach, except that defined classes in Sanskrit are so exhaustive that they cover the material and abstract --indeed cosmic-- experiences known to man. So in Sanskrit the connection is more than etymological.

It was Panini who formalised Sanskrit's grammer and usage about 2500 years ago. No new 'classes' have needed to be added to it since then. "Panini should be thought of as the forerunner of the modern formal language theory used to specify computer languages," say J J O'Connor and E F Robertson. Their article also quotes: "Sanskrit's potential for scientific use was greatly enhanced as a result of the thorough systemisation of its grammar by Panini. ... On the basis of just under 4000 sutras [rules expressed as aphorisms ], he built virtually the whole structure of the Sanskrit language, whose general 'shape' hardly changed for the next two thousand years."

Every 'philosophy' in Sanskrit is in fact a 'theory of everything'. [The many strands are synthesised in Vedanta --Veda + anta--, which means the 'last word in Vedas'.] Mimamsa, which is a part of the Vedas, even ignores the God idea. The reality as we know was not created by anyone --it always was--, but may be shaped by everyone out of free will. Which is a way of saying --in OOP terms-- that you may not touch the mother or core classes but may create any variety of instances of them. It is significant that no new 'classes' have had to be created. Thathachar believes it is not a 'language' as we know the term but the only front-end to a huge, interlinked, analogue knowledge base. The current time in human history is ripe, he feels for India's young techno wizards to turn to researching Mimamsa and developing the ultimate programming language around it; nay, an operating system itself.

Professor's wish-list

1-- Funds are always short for running the Academy and creating new facilities. The Professor spends most of his time running around to raise the required funds and is beginning to tire of this non-creative work. He seeks generous well-wishers to come forward to relieve him of this chore. A detailed proposal for potential donors is available which lists requirement of funds for capital and recurring costs. You may email the Professor directly to receive the document.

2-- Academy's website is somewhat dated and requires a facelift. Professor readily admits the Acdemy does not have in-house skills to build a contemporary site to showcase its works. He seeks enthusiastic youngsters to redesign, host and maintain the website. It would of course mean that volunteers would have an interest in the work of the Academy and are willing to set aside regular time for running the site and also raise the required money for hosting it.

3-- The Professor yearns for young post doctoral computer science researchers at the cutting edge to spend extended periods at the Academy to explore ways of developing natural language computing based on Sanskrit. Modest, comfortable accommodation can be provided though the Academy is not in a position pay any stipends. Better than emailing, it is better to talk over the phone or best, pay a visit after making an appointment.

4--The Professor's greatest dream is to create a Gurukulam at a five acre piece of land available near teh Academy. He would like it to be his final endeavour to show that Sanskrit-learning can lead to viable, contemporarily relevant careers. For something like about Rs. 10 lakhs a new educational system can be pioneered. Prospective donors can also particiapte in developing the curriculum. Please write to the Professor

After effects:

Farm productivity rose. But why? Water stagnation in ponds and channels increased sub-soil mositure. Slow evaporation over long periods of the year changed the micro climate and increased soil animal population. This attracted birds with their own cross fertlisation and seed delivery processes. This brought vigorous undergrowth. Trees grew steadily and shaded the land. Farms retained top soil. Assured of water resources, farmers stayed longer on their holdings. Some have even moved in and made homes. Fodder availability encouraged animal husbandry and that brought in synergistic animal-soil interaction. Farmers living on land are more observant of fine details and shape and mould their land continually.

The food basket is more varied with fruits and vegetables on the table. Many ponds are small fisheries. Income streams are more numerous and with small money surpluses, farmers --as always with all Indians-- have turned to giving their children quality education. Management of schools, health centres, the watershed and community interests invite wide participation.Women have formed themselves into self help groups and run micro credit schemes. The striking impression is that even given that India is ever-smiling, Adihalli-Mylanhalli valley has a high smile-index.

Underlying all this change is the subtlest of all reasons. "Farm ponds are democratic and decentralised," says Reddy. "check-dams are monolithic and autocratic." Also check-dam maintenance calls for community partipation which is good when it happens, but harder to coordinate. Farm ponds and channels are constantly cared for by the owner. Farmers discover a greater sense of control and destiny when they see water standing in their own patch. Water from check-dams if it ever comes to the upper reaches is after all 'piped' water. Water on the land, --with fishes, frogs, dragon-flies and birds-- creates a pond ecology and makes the farmer connect with his inner self. When that happens he excels.

Therefore, BIRD-K's greatest success are the people it has created. There are today about 800 locals who are farm pond experts. Bus loads of curious visitors, NGO personnel and eager farmers arrive every year at Adihalli-Mylanhalli. They receive ready exposition of all matters involved. But perhaps, none can match a barely literate, colourful character who farms a small patch in the valley, they call 'Campaign' Thimmaiah. He is a member of the watershed committee that makes the rules. One of them for instance, is that no one may use a powered device to pump water from the drainage lake in the valley. Thimmaiah polices the lake and is everywhere in the watershed busying himself and preaching the virtues of farm ponds to anyone who cares to listen -- or even doesn't. BIRD-K uses him as a mascot and a living testimonial. It is people like him --who have sprung up from the soil-- that truly matter for a transforming India. They share their time, knowledge and enthusiasm. It is comforting that people like 'Campaign' Thimmaiah ignore the doomsdayers and over-educated Cassandras. They are too busy helping people solving problems.

___

BAIF Institute for Rural Development - Karnataka [BIRD-K]

Post Box 3,

Sharadanagara,

Tiptur 572 202

Karnataka

Phone - [08134] 250659, 251337

email: baif@bgl.vsnl.net.in

July,2003

Other streams:

Southern and coastal AP have swung into action. Chittoor, Vijayanagaram, Vishakapatnam, Prakasam Srikakulam are all names that are lighting up on the SVO map. Members of the VELUGU self-help scheme have coined a slogan : "mana noone, mana vidyut" [My seeds, my electricity]. Under the Karnataka Watershed Development Agency [KAWAD] 10 oil mills run by women SHG have come up. They are in Bijapur, Bellary and Chitradurga districts of Karnataka. They cost Rs.350,000 each and generate revenue of Rs.600 to Rs.800 a day, out of which the SHG pay back the loans. Dr Vidya Swamy at SuTRA, Bangalore is systematically developing best nursery parctices and trying out ways to train grafted trees into short bushes. She also reaches out to women SHGs and explains profitable rural technologies so that with SVO at the centre, an integrated plan can develop.

In under five years of Prof Shrinivasa demonstrating the concept, the idea has begun to deliver results and make hard economic sense. It has probably had the fastest run from lab to land for any idea in India. Indian Railways is moving ahead to use SVO as a blend with diesel. It is India's largest consumer of diesel; so it makes sense for them to look at SVO. The Government has woken up to the potential and there is talk that the Prime Minister is also smitten by it. Prof. Shrinivasa is the convener of the committee set up to draft a National Biodiesel Policy. The venerable BBC came calling recently to record this emerging success story.

SVO, biodiesels, biofuels etc

The Ghond tribe we met in the main story are using straight vegetable oil or SVO. This is oil milled, nominally filtered and used straight in an engine. A purist would be offended by the use of the term 'biodiesel' for this. But it is early days yet in India and 'biodiesel' is a rather evocative name that catches attention. But let us get some facts laid out.

In a warm country like India, use of SVO in applications like gensets will cause no harm. In critical applications like running jeeps, tractors etc however it may be wise to use a two tank system, as briefly described in the article.

In the West, the scene is quite different. The weather is often cold, cooking oil is thrown away after one use and vehicles are over-powered. Biodiesels address all the three situations. Making biodiesel is no rocket science. Many make them at home and the process -- called 'transesterification' -- removes many components from the SVO and renders them a "methyl ester". For those with more interest in the arcana of biodiesel chemistry, the two good pages to visit are at veggievan.org and journeytoforever.org.

Remember however that both SVO and biodiesels are pure renewable fuels. A day may come in India too -- when the SVO idea has caught on -- when small rural businesses will come up offering technically true 'biodiesels' for say, high way trucks.

Returning now to SVO, there are about 20 species of trees whose seeds will yield acceptable SVO. Of these, Pongamia has many advantages and these are described in GoodNewsIndia's earlier story on the same subject. Neem oil too will do well as an SVO but it is more valuable as a pesticde and sells for about Rs.50 a litre. Mahua is good as well but it is cooking grade and in India that is priority use. Jatropha [-- or Ratanjyot in Hindi] is emerging as a popular SVO now. It is a shrub that begins to yield in 6 months though its life is only 15 years. But Jatropha oil is lighter than Pongamia oil and in Erode, Tamil Nadu one gentleman at least rides his diesel Bullet motorcycle fed entirely on Jatropha oil.

New ventures:

In late 2002 AIMVCF made its first investment. Servals Automation in Chennai has licensed and patented two grass roots inventions. One is a water saving, energy efficient 'rain gun' invented by a farmer in Karnataka. It helps in optimising irrigation of cane fields. The other is the Venus kerosene burner that saves fuel and can be used in homes and small

Its second investment is in an ongoing business. Shri Kamadhenu Electronics Private Ltd [SKEPL] in Mumbai has revolutionised the management of village dairy co-operatives. It has been marketing a computerised milk assaying and billing system that has changed the way milk gathering operates. Queueing times have slashed from hours to minutes, milk spoilage reduced and transparency brought about. Farmers come in flaunting plastic cards and go away in minutes with a printed receipt for the milk supplied. SKEPL's machine is called Akashganga ['Milky Way'] and its impact is worth reading in full. It's a truly Indian innovation that uses a DOS based operating system leveraged to serve a huge industry.

After all there are close to a 100,000 village milk co-operatives in 200 districts across India through which over 10 million members market 17 million litres of milk daily. *Take that in*. So, although there are over 500 Akashgangas at work now, they are mostly in Gujarat, a small slice of the huge market. AIMVCF's investment is presumably to take Akashganga country wide. They have invested Rs.1.8 million for a 26% share of equity. Two more investments are likely to be finalised soon.

Aavishkaar has come to imbibe Dr. C K Prahlad's prescription for rapid growth of Indian economy. Concentrate on the Tier-4 market, he says. Tier-4 is peopled by low income masses. Collectively their buying power is enormous and they will buy products and services that improve their lives. Aavishkaar is applying to entrepreneurs within this market, processes like due diligence studies, technical and market opportunity evaluations and management accountability. It manages to pay its lean, professional staff reasonably well, from the interest the uninvested corpus yields. It channels its funds only to businesses that are socially relevant, environmentally friendly and commercially viable. Because in the end, its mission is not only economic returns for its investors but social returns for India as well.

V Anantha Nageswaran

Director

Aavishkaar International

Phone:+65-62352876

Mobile:+65-9731 4261

Email: nageswar@singnet.com.sg

He mastered the TNPA and availed of every scheme for the village. "There are enough well meaning schemes announced by the Government. It is up to the local leadership to go and get them," he says. He has been an efficient conduit between his people and available opportunities.

One of the housing concepts that the Tamil Nadu Government promoted was Samathuvapurams [Harmony Estates]. The idea was to make different castes and religions to live together in a campus of about 50 dwellings each. Over 150 came up all over the State. Most were shoddily built mockeries left to fast buck contractors in cahoots with local leadership. Elango demanded --and got-- a say in the design and execution. He got HUDCO to design a soulful campus. Local soil was pressed by people into mud blocks to build the houses. The community hall was designed to be an activity centre where now vocational courses and village businesses are run. The money set aside for that darling of the Government --a commemorative arch-- was used to build a meeting place. Of the Rs.88 Lakhs that the project cost, over a fourth was spent on wages for villagers. More was saved by using local materials. Villagers assimilated many cost effective building technologies. Houses in this Samathuvapuram are about 40% larger and are better designed.

So it is with all activities in Kuthambakkam. Extensive water management works, processing of agricultural produce, collective businesses run by women, all emphasise local involvement.

Economics for village clusters:

This approach recurs in Elango's economic thinking which is deeply influenced by J C Kumarappa. "If you bring in the contractors you are exporting jobs," he says. He got a door-to-door survey done in the village and found the village consumes Rs.60 Lakhs worth of goods and services per month. Elango discovered to his astonishment, that nearly Rs 50 L of that can be produced at the village level. Since then, he has been evolving an economic theory of village clusters. In simple terms about seven or eight villages form a free trade zone. They identify and produce goods and services without overlap. They consume each other's produce. And the money stays back and gets invested in human development. Ever the Gandhian and a Kumarappa acolyte, he challenges the theory of competition as being good at all levels. For villages it is co-operation that holds the key. Extreme Competition Theorists are heartless. 'People have to be able to begin again," says Elango. "especially if they are able to see where things went wrong the first time."

Who was Dr. J C Kumarappa?

Joseph Chelladurai Cornelius was born on Jan 4, 1892 of Tamil stock. He practiced as an accountant in Bombay and later went to the USA to study economics. He earned his doctorate, returned to India, switched to Khadi clothes and became a fervent nationalist. He called himself J C Kumarappa thereafter.

One day in 1929, he arrived at the Sabarmati Ashram and gave Gandhi his doctoral thesis. Gandhi is said to have read it all night in amazement. He found Kumarappa echoing his convictions. Kumarappa had asserted that man was not a wealth producing animal but a social being with spiritual, moral and political instincts. Economics had to take this into consideration. Kumarappa theorised that in an economy of permanence there was planned co-operation. In an economy of transience there was mindless competition.

Kumarappa worked closely with Gandhi throughout his life. But a newly independent India with vaulting socialistic visions had no place for Dr. Kumarappa. He faded away from public view and died in 1961 preaching and demonstrating his theory in Tamil Nadu.

In 1996 Elango read his classic, "The Economy of Permanence" and was transformed. He is attempting to plan anew using Kumarappa's ideas.

The training centre in Kuthambakkam is named after Dr. J C Kumarappa.

Now, the punch question. How replicable is the Ralegan process? Is it possible to find an Anna in every village? Also Ralegan has few Dalits and no Muslims or Christians. How do you take the value set from here and plant them elsewhere?

He listens carefully. And begins. You know it's going to be a long answer.

"I began to ask myself these questions once Ralegan was on its way. I decided to find out. So I asked ten college Principals to send me their alumni list. I sent out a thousand form letters. I asked them if they would be interested in propagating the Ralegan experiment. They would be trained for six months. Each day would run from 5 am to 10 pm.They must learn to clean the streets and toilets. Live a simple life and expect little money. After training they would have to spend years in villages as hard as Ralegan was before 1975. They would be paid reasonably. Would they be prepared for this challenge of rebuilding India?

"Not a very good copy, you'd say for a recruitment ad, but I got 403 responses. I picked a 110. When the street cleaning part began 14 left. As the course ground forward, a few more left. But in the end I had 75 potential leaders with me. There are three Muslims and 5 girls among them. Is this not remarkable? I had cast the net randomly and found 75 young Indians ready to work for others. All this from Maharashtra alone with one form letter.

"The criteria for selecting the villages for development were severe. They had to be a minimum of 20 km from any big town. The villages needed to have a population below 4000 and had to be located in a drought-prone district - we want to transform them by focussing on watershed development. Our trainees screened many villages and selected 75 clusters. Each covers a 2500 hectare area. They are all over Maharashtra. Some were deliberately chosen for mixed populations. I visited everyone of them.

"Our young leaders moved in and prepared action plans after surveying and auditing the project areas. I interacted with CAPART [Council for Advancement of People's Action and Rural Technology] and have already raised money for 25 of the project areas. At between Rs.10 and 15 millions per project, I have enough to start. 4 have been underway since late 2001. Others will be starting soon."