No cloth is ever wasted. They are converted to school bags, tote bags, quilts, and mats. A great quantity is converted into narrow tapes to be used as drawstrings for petticoats. The ultimate, unusable waste is chopped up and stuffed into pillows and quilts.

Perhaps, the most poignant of all products that Goonj makes are sanitary napkins of its own design. Each set has three parts: a waist-string, a small absorbant pad and a palm wide strip to hold the padding in place while its ends are tucked under the waist-string. Ten sets are packed with care into a drawstring pouch for a women to receive without embarrassment. [It'd be nice if readers of GoodNewsIndia came forward to sponsor this revolutionary product at the rate of Rs.20 per bag, with a minimum of say, 100 bags. You could be saving women from dying of a lethal ailment called neglect.]

For all the care that Goonj lavishes on its gifts of love, quantities are nothing to be sneered at: they currently send ten tonnes of material per month. But the need for this service is huge in India: "All the quantity we send is sufficient for just two or three good sized villages", says Anshu and adds: "A disaster like the tsunami brings out an overkill and then collective philanthropy drops to zero". [See box]

Cleaning up after the tsunami:

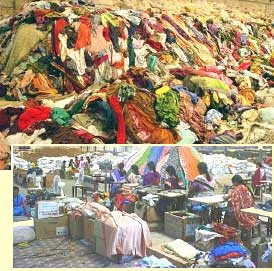

The tsunami of 2004 left behind not only changed lives but also the fall-out of misplaced, insensitive giving. People from all over sent trainloads of clothes,a quantity far in excess of the need - much of them no one could use in south India [woolen balaclavas, for example].

Governments get blamed for many things but in this case there was no one else ready to clean-up. So district collectorates in Tamil Nadu gathered all the remaining mountains of clothes and shifted them to warehouses. And there they lay, with no one knowing what to do with them.\

To Anshu, all this was painful irony: here he was with a fistful of wish lists from villages that he was unable to meet and in government godowns lay orphaned clothes. When he heard that a collector was selling them off in lots to pay for relief works, Anshu was enraged. He pointed out that merchants were buying good clothes for Rs.2 that they could resell for Rs.40. Besides how can the government make money out of aid material. The special tsunami collector Mr C V Shankar, in Chennai saw the point and asked what was the solution? Anshu said, "Hand them over to Goonj and we will clear the pile and account for every single piece". Then someone said what came to Tamil Nadu cannot go to other parts of India. Anshu retorted by holding up heavy woolens and asked where they might have come from.

After several rounds with sympathetic Mr Shankar, he got the go-ahead in June, 2005. The state has also given a part of a warehouse ib Chennai for Goonj to set up sorting and clearing operations. Anshu started with just Rs.10,000 from a well-wisher. He recruited local girls and trained them in the tested Goonj workflow. The collector was impressed and soon the word went around. In January, 2006 Deutsche Bank heard of it and a senior manager flew in from Singapore for a presentation by Anshu. Instantly Rs.20 lakhs were sanctioned.

With that Goonj has bought 16 sewing machines to begin a conversions section for its product line and of course, their favourite, the sanitary napkins. Today the place is abuzz with 40 women at gainful employment. Goonj took over a 2 million pieces pile. The pile is diminishing at the rate of 4,000 pieces per day and reaching needy people all over the country. [During the last earthquake, a consignment went to Pakistan as well.]

This has become a model of innovative, creative public service.